Jump to:

Basic Archaic Greek Clothing

Basic Roman Clothing

One of the most popular periods for hot weather clothing options is the Roman Empire, but Classical Greek and even Pharonic Egyptian are starting to pick up steam in the SCA. Even though they are not Medieval or part of what would be considered the Middle Ages by most individuals, the ancients no doubt shaped the way that Europe evolved into the medieval period, and still has a profound impact GLOBALLY today. It has been a passion of mine since I was in elementary school, one of the main focuses of my academic studies, and I’m thrilled to be able to share my information about Bronze Age and Ancient societies on this site.

What is the Ancient period? Well, that’s a really broad term. “Ancient” can be anything pre-modern, including the Middle Ages, but most people view the ancient civilizations as being Rome and earlier. There are multiple “ages” within cultures within the Ancient period, so rather than draw fractals or crazy timelines, I’m using “ancient” as a blanket term for this page as I explore and collect information during my research and experimentation.

For example, ages within “Ancient Greece” include The Bronze Age (Minoan/Mycenaean), The Geometric Age, Archaic Age, Classical Age, and Hellenistic Age. “Ancient Rome” had the Kingdom, Republic, Empire, and Late Antiquity/Early Byzantium. Egypt had the Old, Middle, and New Kingdoms, and then on top of those “big three” are the Ancient Near Eastern Mesopotamian cultures (Sumer, Akkadia, Babylon, Assyria, etc), Hittites, Hebrews, Achaemenid Persians, etc. AND all of the Asiatic or Northern Eurasian Iron and Bronze Age settlements. There is no loss for ideas for those that want to explore the Ancient World! For the sake of brevity and my own academic limits, this page will be devoted solely to the Ancient Mediterranean with a smattering of the Near East.

Benefits of Ancient Mediterranean clothing in the SCA:

Comfort

Durability

Excellent for hot weather

Easy to sew

Endless embellishment opportunities

Basic Archaic Greek:

The Archaic Age (pretty much the 7th-6th-5th centuries BC) is basically when a lot of what we know of as “Ancient Greece” begins to take shape. This is when Homer composed the Iliad and the Odyssey, when Sappho lived, and when sculpture started to make an appearance.

And now, a crash course in art history!

The pivotal sculpture forms of the Archaic Age are the Kouros and Kore statues, or “young man” and “young woman” respectively. There is some speculation on who they represent, but the general idea seems to be Apollo or Dionysus for the Kouros, and Persephone for the Kore. Or, nobody in particular after all. Kouros is almost always stark nekkid, while Kore has been draped with a variety of garments. The style was pretty much lifted directly from Egypt, and predated the more common contraposto-style statues you see from the late Classical period.

Thanks to the miracles of modern science, we’ve been able to really get an idea of what colors the statues were painted, and boy oh boy, are they a treat to the eyes. (Photos below are my own, taking at the “Gods in Color” exhibition when it was at the Legion of Honor in San Francisco.)

The colors! The trim! Sure, most of it is allegorical to the goddess or person they are portraying and not actually indicative of patterns worn by actual people, but, the options for fun for hot weather garb! I would avoid wearing all of the lotuses that Phrasikleia Kore has on her, only because it’s a funeral stele and they’re symbolic of the afterlife, but the fit of her chiton got me thinking that there is no need to be swimming in fabric. Contrast her to the draped layers on the Chios Kore, means that there were possibly options, and not just limited to the skill of the sculptor, noted by the folds at the bottom of Phrasikleia Kore’s chiton.

Inspired by this fit, and bored with a stack of fabric at my parents’ house when house-sitting back in June. I decided to make a slimmer fitting chiton by taking 2 yards of 58″ wide linen, folded the short way. I determined that I could do this with less than 2 yards for my figure at this width. I know that not all women are created equal, so I apologize if this particular hack doesn’t work for you, but the style is still doable. For me, I found that I could go about 32″ per front and back panel and still have plenty of ease with my 42″ bust and even wider hips. This is a heck of a lot cheaper and less cumbersome than one of my 4-yard Roman style chitoi/tunicae interior.

I threw some trim on the top and bottom, and added a slit to one side seam for walking ease, and thus, my “archaic” chiton was born. Half the fabric as a Roman one, and still a flattering fit.

I sewed the top of the first one, instead of adding buttons or pins, and this allowed me to wear a real bra at Pennsic, instead of a tube bra, which relieved some of the uncomfortable under-the-boob sweat that women are subjected to. I lived in this thing at war.

So, before you all run off to try this, I want to make a disclaimer, while I called this my Archaic Chiton, I’m only doing so because of the slimmer fit. In Greece, they sewed no seams. Everything was wrapped, pinned, and belted. I do not, and never will, have the huevos to pull that off.

Here is a drawing of my measurements, and basically how I did it, for those that want to try the slimmer look, as well.

This pattern works just as well for men, just make the chiton knee length without a slit, versus full length.

Basic Roman:

Here is an introduction to the popular garments of Roman citizens from about 100BC to CE 400. Think of it as a quick reference guide. For a more in depth look, I recommend the book “The World of Roman Costume” by Judith Sebesta and Larissa Bonfante, which you can easily get at Amazon.com for about $30. Scans on this page are taken from that book. It’s really an awesome source!

For those who have attended my classes (YAY!) I have my “module” available via Google Drive now, where it can stay forever. You can access that here: https://docs.google.com/file/d/0B4jf5ZhBMl5xNHZKMGxkcjFKUGs/edit?usp=sharing. Please note it does contain some of my academic papers, as well as my class outline from Pennsic 41 that has my old persona name on it.

And here is a video of me teaching at class at Market Day at Birka in the East Kingdom:

Materials

Wool was the preferred fabric of Romans, as sheep were a HUGE part of their economy. Linen was also readily available, but do to its inability to take dyes well, and the dangerous and rather disgusting methods of the creation of linen fabrics from flax and laundering them, it’s easy to see why it may not have been as popular as daily wear. For the sake of modern weaves and costs, linen is an excellent choice for the modern re-enactor or re-creator. If you can find a nice tropical weight wool made from a basic weave, that’s your best bet if you want to take that option, but it’s often difficult to find. Trust me, I know. 😦 Linen blends are not a terrible option. The linen/rayon blend available at Joann’s gets a great deal of praise and shames from SCAdians all over. Most of the shame is that rayon is not period, but, as far as price goes, you can’t beat it. The rayon helps maintain a lovely drape of the garment and controls the linen’s shrinkage. I have several garments made from this material, and they’ve survived events ranging from formal balls to Pennsic, and frankly, if someone feels it necessary to snark you over that fabric choice, you have my permission to hit them with a giant hammer. 🙂

Cotton is an interesting topic of discussion, being that it had been cultivated in Egypt during the Roman occupation. There is evidence that cotton was often blended with flax to create a fabric known today as fustian. However, period cotton was spun differently than it is today, so do not consider 100% cotton or Egyptian cotton as an alternative for clothing, no matter the cost. You will regret this, as it is not nearly as durable as wool and linen. It will bleed, stain, wear, and tear more than linen. It also wrinkles terribly. Blargh. I do have a fustian chiton that’s beautiful and airy, but the wrinkles…eep.

Basic Garments and Their Construction

To begin, the foundation of all Roman clothing is known as the tunica. Creative, I know, but Latin isn’t the most diverse language when it comes to such terms, which is why you will find that when addressing ancient European clothing, the Greek terms are often employed. Although Greek was very widely spoken during the Roman Empire, even more so than Latin in the later years, I am unsure as to what they would have called their garments. Much like when the Japanese were approached by Westerners about what they called their clothing, and the term kimono was used, basically meaning, “what we wear.” We use tunica as an equally “general” term when discussing Roman clothing, in the case of women who have more than one distinct type of garment, we use the terms stola, peplos, and chiton. The later two of Greek origin, and more popular for the discussion of garments in the SCA.

Viri (Men)

Men’s clothing in Rome was relatively simple, but most people immediately associate men’s dress with the most symbolic garment of the period: The toga. So that is where I will start first to attempt to dispel all the dumb myths about it.

The Toga, first and foremost, is NOT Greek, no matter what John Belushi led you to believe. There was a similar Greek garment known as a himation, but it is not worn in the same fashion, nor cut in the manner you see above. The toga is also a MAN’S ONLY GARMENT. Women did NOT wear this. If a woman was togate (in the toga) she was in disgrace. So, remember that if you’re looking for ideas for a toga party. 😉

The toga is a symbol of state. It was worn only by free men in the Republic through the early days of the Empire. Before it completely fell out of fashion, it was worn strictly as a ceremonial garment, or by senators and candidates for office only. The term “candidate” itself is a Latin derivative from “candidas” the stark white toga worn by those sought to be elected to office. Senators would wear the toga with a red or purple stripe along the long edge to signify their office, and only the emperor could wear an entire purple toga.

This was not particularly a comfortable garment, being cumbersome, and men often complained that they would either be too hot or cold wearing it, so it fell out of fashion around the time of Emperor Hadrian. It’s approximately 9 yards of wool, and can be recreated successfully using the pattern above. So yeah, take that Scots, the Romans were wearing the “whole 9 yards” first. 😉

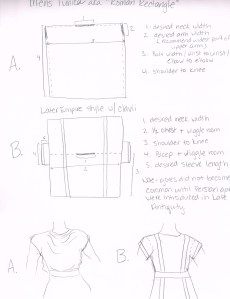

A man’s tunica is extremely simple in design. My friends and I have dubbed it the “Roman rectangle” and the picture below I illustrated demonstrates pretty much why. It’s basically 1 length of cloth folded, or two sewn up the sides and shoulders with a slit for the head and arms. That’s it. Belting it is what gives the illusion of sleeves. Now, toward the later period of the empire, sleeves were becoming more common as a result of extended time at the Northern Frontier, and the influx of Christianity leading people to cover their arms to demonstrate humility. My illustration also slows the clavii stripes, which at first signified membership of the equestrian class, but later became more of a fashionable embellishment.

Feminae (Women)

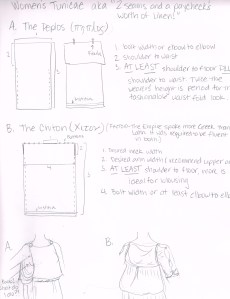

Much like today, women in Rome had quite a few options when it came to clothing. Lower class women would have work a tunica much like the men’s style above, but most commonly, you would see them in one of two popular designs, the peplos and the chiton. You might have heard the terms “doric tunica” and “ionic tunica” used to describe these same garments respectively, but there is no proof these terms were used in period, and were probably fabricated by the Victorians at the same time they named the column styles we had to memorize in grade school social studies. More than likely, Latin-speaking women of Rome would have referred to their garments as tunicae or perhaps tunica exterior/interior if they were layers. Greek-speaking citizens would have used the previously mentioned terms, peplos and chiton.

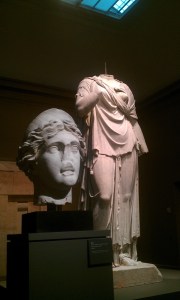

The peplos is probably the most widely spread garment of women everywhere in Europe from early Antiquity well into the Middle Ages. (My handout for my class on The Peplos is available in the link above.) This garment is essentially a tube dress pinned or sewn at the shoulders, with flaps (Peplums! Know your derivatives!) folding over the back and front which allowed for ease of adjustment and more than likely, breast feeding. This can be made of quite some length, as archaeological record has shown this style of dress girdled at the waist and bloused before being brought to the shoulders. In a period in which more fabric meant more money, you can see why this would be impressive. Below is a photo I took from the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York showing this style of blousing on a Roman copy of a Greek original. (Isn’t the sculpting on this mindblowing?)

However, recent research of mine, through the comparing of archaeological and artistic records, have led to be begin believe that the peplos may have been the garment of a maiden or unmarried woman in Rome. It was much more popular in artwork portraying “virgin” goddesses, such as Artemis/Diana and Athena/Minerva rather than married goddesses, such as Hera/Juno and Aphrodite/Venus, almost always seen with a chiton. I’m not implying this is absolutely certain, but it’s a strong hypothesis.

The chiton is the same pattern as the men’s “rectangle,” only with buttons or pins on the sleeves, rather than a closed seam. This also could be made with a great deal of additional length to allow for the desirable blousing at the waist. This garment is also seen with elaborate girdling done around the breast area to shape sleeves and perhaps allow for more support.

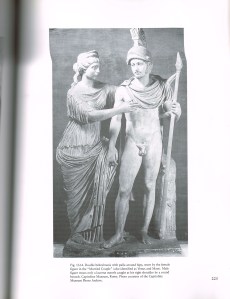

Here is a fantastic image of Venus tending to Mars wearing a beautiful example of a chiton, and how provocative the garment could be.

The Roman woman’s equivalent of the toga was called the stola. This, rather than being a cumbersome wrap, was a cumbersome dress, about twice the height of the woman, that would be girdled and bloused at the waist, and gathered at the shoulders to allow for a desirable v-neck effect. This was the garment of a matron, or, married woman with more than 4 children, and it was considered a great honor to have the privilege to wear it. But, much like the toga, it was not popular. It was considered unattractive and essentially gives the wearer an blimp-like silhouette, and only seemed to have survived just barely into the Flavian Dynasty (mid 1st Century.) Somewhere, in the bowels of the internet, exists a photo of myself demonstrating the firepower of a fully armed and operational Roman stola that basically makes my hips look like the Hindenburg.

Once the stola fell out of favor, it looked like women still layered clothing, and by looks of it, in the form of a peplos over a chiton. There is a new statue at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts of Juno which shows this. Here is a picture I took this past June (ironically.) I hope to get back there and actually see her head attached soon.

The last piece of a woman’s clothing would be the palla, a 3-6 yard long piece of linen or silk (if she could afford it) that acted as a wrap or shawl. The smaller lengths would be wrapped and pinned across the body for everyday where, and the longer lengths were worn out of the house to cover the head and body as was dictated by sumptuary laws. Much like medieval Christian and Islamic traditions today, a woman would never leave the home with her head uncovered, it was considered bad taste otherwise. The palla could be simple, or heavily ornamented.

Here’s another video of me explaining how I belt my chiton, and a quick look at my stola.

Coming soon:

Shoes

Jewelry

Common colors worn

This was an extremely helpful. I am in the SCA and have been tossing around the idea of switching my persona from English/French, to Roman. Thanks for posting this. I’ve shared it with other other members of our group who are looking into the Roman garb.

–Heather Marius (Shire of Okenshield, Midrealm)

LikeLike

I’m glad you folks are enjoying it! Please let me know if you have any questions or need help.

LikeLike

Thank you so much for this! I wanted to do it up big for a roman themed murder mystery and this was very helpful!

LikeLike

Thank you so much. This video really helped me through my Pennsic withdrawal.

LikeLike

I have a question about the use of silk in Roman garb. I know that silk was popular among the upper class, but which modern type of silk would be used to accurately recreate Roman garb? I have 5 yards of silk habotai that I bought from Dhatma Trading Co., but I don’t know it it has the right look for a peplos…

LikeLike

Habotai is going to be extremely light and sheer, so if you do decide to go with it, make sure you layer it over a chiton, which is a period solution. (See my post on the statue of Juno at the MFA.) It’s not always comfortable to wear silk right against your skin anyway, plus, laundering it is a NIGHTMARE!

As for period silks, a charmeuse or light crepe might be your best bet, it’s much softer and satin like, and is not slubbed like decorator silks such as shantung or dupioni which you see in a lot of garb. (Guilty as charged.)

If you feel that the habotai is going to be too sheer and you’re looking for another option that won’t break the bank like charmeuse can, I recommend checking out vintage silk saris. This is an SCA “trend” right now, but it does have some periodicity as Roman women did wear colorfully embellished clothing. Just stay away from things such as heavy beadwork, sequins, and glaringly modern prints.

LikeLike

You’ve stated that there is room for embellishments. Have you found any examples of embroidery?

Awesome research! Thank you for collecting it. I will be sending folks to take a look.

LikeLike

Appliqueing tapestry woven bands or weaving a pattern directly into the fabric of the garment seems to be the primary method of embellishing. Now, there is Coptic embroidery, which came around later, practically Byzantine times, in Egypt, but it’s considered stunt documentation to assume that it made it back to the Italian peninsula.

LikeLike

Thank you! I have never been able to figure out how to tie it.

LikeLike

I’m interested in a couple of things, the first of which you might have mentioned above but I didn’t see it (tired eyes). Some of the reading I’ve done lately indicates that basically all first-century CE garments were white/undyed/unbleached, but above you’ve got a picture of Jeff wearing a color. Knowing your penchant for accuracy, I am assuming this means that those sources I’ve been reading are likely incorrect. Moreover, though he doesn’t care about 100% historical accuracy in garb and has never made a real study of it, Hakim is a bit of a Roman hobbyist, and insists that at least in Macedonia, colored tunics were more the thing. Can I hope that that’s true? For men, women, or both?

The other question is one you might or might not be able to answer, but I’m betting you can. Hakim, my husband in the SCA, is portrayed by my real-life wife, who is somewhat busty and hippy. To make room in a tunic for those curves, what would you suggest would be better: to just enlarge the garment overall, or to add discreet underarm gussets?

These questions would be for 1st century, free people with minimal rank (AOA), and he still hasn’t chosen a profession for his overall persona, let alone for his occasional trips to Ancient Rome. I’m of the same rank, and I probably shouldn’t choose a profession before he does, so that we remain roughly comparable in social class.

LikeLike

First answer: We have enough artistic evidence of dyed fabrics from Ancient Greece through early Rome to prove this otherwise. They painted the statues, and we have colorful frescoes as far back as the Minoan period. Hell, we have colored fibers that remain from the Mesopotamian period, so the idea of keeping bleached garments through the Republic into the Empire is foolish and Victorian in origin. Bleaching required a lot more work than dying, and was destructive. It was a disgusting job that required collecting urine and letting it go stale, for example. After that, you only see “stark white” anything when the Toga Candida was being worn, which was when somebody was a candidate for office. This is where we get the term from.

Second answer: You’re not going to be able to hide a woman’s figure or accommodate it properly using the traditional “Roman rectangle” tunic worn by men. There’s a reason why women belted their tunica exterii/chitoi the way that they did immediately under the bust. Gores were not added until about the 6th-7th century when Persian influence was becoming more and more visible in the Byzantine Empire. The best thing I can suggest is that rather than having Hakim wear a traditional woman’s bra, try to bind the breasts flat to eliminate the upper curves. You can’t bind the hips, but it may look a bit better than having a totally feminine figure. They did not have underarm gussets, because the sleeves were just slits in the cut of the side seam. My “Roman rectangle” pattern is above. You could make it wider, which would create a nice billowing effect of wealth, but it can also make you look like a sack if you aren’t broad enough. I recommend measuring Hakim with his arms out, elbow-to-elbow, for an ideal width.

LikeLike

This was very informational!! I love the detailed explanations and the videos. Thank you for posting this!! I appreciate the hours you spent at the Met. You did good 🙂

LikeLike

would unmarried Roman women have covered their hair? What about slave girls (especially if she was from a modest culture)

LikeLike

I thought I made a reply here, but I guess it didn’t catch. Anyways, coverage in Rome was not like what we think of with the rest of the Middle Ages, or Islam today. You only covered outdoors using the palla, and it was just as much for sun protection as it was for modesty. An unmarried woman of status to own the extra fabric would have done it just as much as a married woman would. Young girls probably would not have. Being that a standalone peplos may have been considered a virginal garment, you could pick up the back peplum and wear it over your head for elemental protection, as well.

As far as slaves go, they forsook their original culture when they were enslaved, and were at their masters’ bidding. Depending on the roll of the female slave, and her owners, she may or may not have covered. They were not chattel slaves as we’re accustomed to with American History, and tended to be treated better, including being paid for some jobs, which allowed them to save up for their freedom. It really comes down to the owner and their terms. I recommend doing some additional reading on this.

Noting your additional reply asking for citation information, while I appreciate using my blog and citing properly, please follow-up on this reply and complete the research yourself. I wouldn’t want you to be busted for academic dishonesty. (As a professor myself, I checked blog sources.) Have a great day!

LikeLike

Also how do I cite this blog? I need to know the date of publication (day/month/year) and the author’s name.

Thank you very much for writing this.

LikeLike

Angela Costello, 14/01/2013.

Thank you for citing your sources properly!

LikeLike

thank you so much for including your class video – I’m prepping for Pennsic, and have already learned so much!! One quick question – you mentioned the use of stripes on men’s togas, but is there any evidence of decorative stripes on women’s clothing? You had mentioned woven bands and embroidery, but I was wondering about solid or nearly solid stripes as well. Thanks!

Amalie von Hohensee

LikeLike

Stripes as in striped cloth? Or clavii stripes? In the case of clavii, we have a lot of evidence of women wearing them in the late Roman period 2nd-5th century), predominantly in Egypt. During most of the Republic and early Empire, they were a symbol of rank, and worn by men alone.

LikeLike

I’m trying to figure out what’s going on with the statue of Juno. I can see the chiton with gap sleeves. Is that an unbelted peplos on top, which only goes down to mid-calf and the fold to her groin? What’s the big brooch on her right shoulder–is that holding her pallos, which is draped under her left arm?

LikeLike

I did an entire blog post on this. Did you see it? I break it down with color coding the garments. It is an unbelted peplos over the buttoned chiton. This is considered a matronly fashion after the stola went out of style.

LikeLike

No I didn’t–THANK YOU!!!

LikeLike

Hello,

To be honest, I had been considering a Roman goddess and then just a Roman citizen for Halloween when I started to do my research and now I’m obsessed with authenticity. I love quality in all aspect of costume and strive for that whatever I am doing for myself and my daughter. I apologize if you have addressed this in another place but I had a few ideas that my albeit limited research so far has lead me to wonder about.

I see what you have suggested for linen and linen substitutes and also what you also recommend for silk. My question is what is authentic for wool of the time? Would a light weight merino wool serve? I am absolutely fascinated with the subject and want to create a period piece for myself.

Thank you for all your hard work and sharing.

LikeLike

Hello and welcome to the rabbit hole! A thin, simple woven wool will be fine, even a solid suiting, as twill weaving was possible. So yes, a light merino would be good. If you can find gauze, even better. They processed wool by hand, and it was their primary fiber, so it was very different than what we get now, if not, better than the machinized wools we have today.

LikeLike

Thank you, and yes, this is quite a rabbit hole.😃

LikeLike